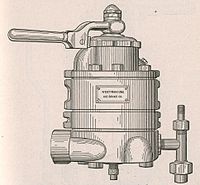

*Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons Two-and-a-half years after establishing the Westinghouse Air Brake Company, inventor and industrialist George Westinghouse received a patent for the railway air brake on March 5, 1872. By modifying an existing system, he increased the safety of the rapidly-expanding railroads by ensuring the massive powerhouse machines would be able to come to a stop with significantly fewer failures. Throughout the first six-plus decades of passenger trains, braking systems were incredibly primitive. In most cases, the trains carried a staff of porters (known as “brakemen” in the United States) to jump from one car to the next pulling levers to stop each link in the train individually. Relying on a basic clamp system to lock up the wheels, the method proved dangerous and unreliable — the men would have to hear a specific low whistle amongst the sounds of the moving train and act quickly. Within a few years, as the railroad developed into a viable means of transportation and engines became larger, the need for more powerful brakes was evident. Following Sir Isaac Newton’s First and Second Laws of Motion, an object would continue moving until a larger force acted on it to bring it to a stop. In the case of multi-ton locomotives capable of moving in excess of 60mph with long strings of boxcars in tow — and, increasingly, up and down through the mountains — a system would have to absorb significant amounts of energy. To designers, this meant a “continuous” brake yanked by the train conductor instead of the strategically-placed porters running from lever to lever in car after car. A pipe running off the engine would be run backward to connect with the first car, which had a pipe to extend to the second and so on. Underneath each car, a cylinder off the main pipe connected to the brakes that, when filled with air by a pull on the conductor’s handbrake, would slam shut and bring the car to a halt. More effective than the brakemen, this early air braking system could be rendered inoperable by a loose connection or weak hose. If, say, the air was not transferred beyond the tenth car due to a malfunction, the brakes would not work whatsoever. Even when working correctly, the pressure released by the conductor would reach the first cars long before the last cars, causing those behind to bump into the one in front or, worse, derailing the train. What Westinghouse did in coming up with a fresh take on the air brake, however, led to a revolution. Focusing on a triple-valve system, he made the brakes capable of closing without being under full pressure. The cylinders would have a partially-filled reservoir of air that responded to the first pull of the brake handle. As air emptied from the long brake pipe, the cylinder filled with the reserve portion of air in the system and applied pressure to the brakes. When the amount of air within the cylinder reached a certain point, it would vent air out and refill the reservoir. Pleased with the design, Westinghouse received a patent on March 5, 1872 for the “automatic” air brake system. With the new triple-valve and an air compressor, Westinghouse dramatically improved the responsiveness of railroad braking systems. Many engineers resisted the idea of carrying additional equipment, but tests proved the stopping power measurably better — more than a hundred yards sooner on a dry track than the nearest competitor. Despite this success and a growing desire amongst industry leaders to make the railroads safer for both passengers and goods, Westinghouse struggled to get carriers to adopt his invention, with vacuum systems considered the preferable option due to lower cost and less weight. Determined to see his invention make the railroads safer, Westinghouse continued improving the design, earning a second patent in 1887 for a faster-acting valve and adding an emergency system to take over in the case of a brake failure. With the Safety Appliance Act of 1893, his fortunes turned. Congress wrote the law to improve travel along the rails, requiring all companies to make an automatic brake system part of their operations. In a little over a decade, the Westinghouse Automatic Brake was on millions of trains and accidents decreased — no small feat considering the amount of railroad traffic increased by leaps and bounds. The foundation for the air brake systems on trains around the world after well more than a century in existence, Westinghouse would immediately recognize the fruit of his labor today: modern designs have only a handful of advances, most of them brought on by the advent of new technologies and materials. Also On This Day: 1770 – British soldiers kill five civilians in the Boston Massacre, increasing colonial hostility on the way to the American Revolutionary War 1616 – Nicolaus Copernicus’ De revolutionibus orbium coelestium is banned by the Catholic Church 1912 – Italian pilots use airships for reconnaissance over Turkey, the first instance of military use for the craft 1953 – Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin dies 1981 – The ZX81, an early home computer produced by Sinclair Research in Britain, is introduced

March 5 1872 – George Westinghouse Patents His Railway Air Brake

*Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons Two-and-a-half years after establishing the Westinghouse Air Brake Company, inventor and industrialist George Westinghouse received a patent for the railway air brake on March 5, 1872.…

530