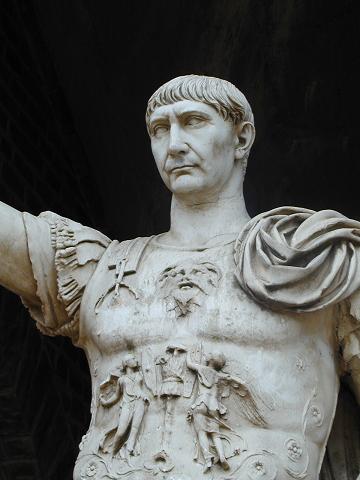

*Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons There are dozens of empires which have shaped the world today, though only Rome could be said to have the greatest effect on Western traditions. Throughout its reign, a variety of men took the helm and steered it to vast financial and territorial dominance, but none managed to expand the Roman footprint as much as Marcus Ulpius Traianus, the emperor who stretched the empire to its greatest size. Born on September 18, 53 in what is now southern Spain, Trajan would go on to become regarded as one of the Five Good Emperors historians have picked out near the middle of Rome’s history. The city of Italica, Hispania Baetica — near Seville — had become a haven for the Ulpis family, serving as the ancestral home for more than 250 years before Trajan’s birth (and lasting long after his death). When he came into the world on September 18, 53, he became the newest member of a very prominent family, welcomed by a father who served as a senator and general for the region. In his late teens and early twenties, he worked his way up in the Roman army, gaining a reputation as a soldier’s commander while fighting in some of the most brutal combat the edges of the Roman Empire had to offer. By the age of 24, he had moved to Syria, where his father was serving as governor and soon took an interest in politics, gaining a position as Tribunus legionis — similar to modern city councils, only with more legislative authority — and eventually begin elected consul and sent to Rome in 91. As he left his adopted home, Trajan brought with him a little-known Greek architect, Apollodorus of Damascus. Pushed into fighting on the northern border with the Germanic tribes, his popularity as a military leader blossomed once again. His former superior, Emperor Nerva, unable to win the loyalty of many of his soldiers with his harsh communication style, saw an opportunity to build support within the army and adopted the young Spaniard as his successor in the fall of 97. Trajan was now in line to be emperor. The following winter, Nerva died of natural causes after just sixteen months on the throne. Arriving in Rome to the cheers of the populace, Trajan immediately won the heart of the people by taking his predecessor’s lead and unwinding the treachery of Domitian, who had been assassinated in 96 after jailing vast numbers of rivals without cause and claiming their property as his own. Extending Nerva’s policy of returning those lands to the rightful owners, Trajan soon released a large number of those who had been imprisoned. On the streets of the capital, evidence of his large vision for Rome soon became unavoidable. Capitalizing on the vast wealth pulled in from territories conquered by the Imperial Army, he ordered several ambitious building projects, employing his old friend Apollodorus to design many of them. Beyond merely constructing landmarks known today as Trajan’s Forum, Trajan’s Market and Trajan’s Column, he invested in the infrastructure in the wider Empire, shoring up roads and bridges to ensure the flow of trade moved with little resistance. As wealth grew, he led an initiative to create programs to feed and educate orphans and poverty-stricken children spread around Italy. (In time, the Roman Senate took to calling him “Traianus optimus” — “Trajan the best.”) On the field of battle, Trajan moved his armies against Dacia, expanding Rome’s borders to the Black Sea before adding other territory in Syria and Egypt with little military effort. After a five-year peace, he led an assault on Parthia. Unhappy with the man wearing the crown of the shared territory of Armenia, he led his soldiers into the east to conquer the Parthians once and for all. In early 116, after three years of fighting, the Empire had grown to include large swathes of Mesopotamia. Beginning on the Atlantic coast of modern Portugal in the west and ending on the shores of the Arabian Sea in east, the Romans controlled much of Europe, North Africa and a large chunk of the Middle East. Contemporaries, such as Cassius Dio, believed he had achieved his goal — ruling the largest iteration of the Roman Empire to date. On August 9, 117, sailing back toward Rome in the hopes of returning to the capital before an illness he had battled for months became more severe, Trajan succumbed to edema the port of Selinus in modern Turkey. As Hadrian took charge and rolled back the scope of Trajan’s conquests by returning Mesopotamia and Armenia to the Parthians, the well-loved emperor from Spain would be cremated and entombed under the column that bears his name commemorating his victory over the Dacians.

September 18, 53 CE – Roman Emperor Trajan, the Second of Five Good Emperors, is Born in Spain

*Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons There are dozens of empires which have shaped the world today, though only Rome could be said to have the greatest effect on Western traditions. Throughout…

520