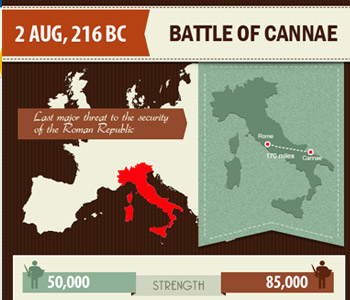

Click to view full Infographic In the southeast of Italy, approximately 170 miles from Rome, the tiny town of Cannae would be the scene for the last major threat to the security of the Roman Republic for nearly six centuries on August 2, 216 BCE. More than 85,000 Roman troops lined up to tackle the armies of Carthage under the leadership of Hannibal only to be swallowed up by the military genius from North Africa. Historians continue to look upon the defeat as one of the most comprehensive in ancient history, both in terms of total Roman losses and the utter destruction wreaked by the tactics employed on the field by one side against the other. The Second Punic War, lasting from 218 to 201 BCE, is famous for a variety of reasons – most notably the rise of Hannibal as the leader of the Carthaginian armies and his ambitious plans to threaten the heart of Italy in the early phases. Having seized the city of Saguntum on the eastern coast of Spain in 219, Hannibal launched forward along the Mediterranean through Gaul and over the Alps, losing as many as three-quarters of his men in the process. Undeterred, he reinforced his troops with Gallic tribes and swept to victory at the Battle of Trebia in late December 218. Six months later, Hannibal would push on to Lake Trasimene and claim much of northern Italy by way of a perfectly-executed ambush on the Roman legions there. Panic ensued in Rome. The Alps, once considered the Empire’s natural defenders in the northwest, had been breached and the invincible armies of the republic routed by the general from North Africa. How long could it be before the capital itself fell into his hands? Staggered by Hannibal’s skill marshaling his troops, Quintus Fabius Maximus Verrucosus – a dictator elected and permitted by law only in cases of emergency – employed a method of attrition by which the Romans would avoid frontal assaults or pitched battles. By depriving Hannibal of the victories which would help him gain allies, Fabius reasoned, the Carthaginian general would be forced to retreat due to lack of supplies. This strategy, though effective, proved politically unpopular. The Romans, accustomed to triumph, were in search of a way to defeat Hannibal as they marched toward Cannae in late July. The general from Carthage had seized the key supply center after sweeping up the Aufidus River several days before. In the capital, fear once again left many wondering if Rome itself would soon be under his control. Two consuls, Varro and Paullus, were sent to meet Hannibal at Cannae, leading an estimated force of nearly 86,000 men – a clear numerical advantage to the 50,000 waiting for them. According to Roman tradition, when two separate armies were combined to form a singular unit, consuls would alternate command from one day to the next. Varro, determined to be the hero who defeated Hannibal, found cause for confidence when he repelled an ambush from the Carthaginians along the way to the field. Now spread across the plain of Cannae, a sense of belief filled the Roman ranks on July 30th. Two days later, Hannibal offered Paullus the opportunity to begin the battle. Unsatisfied with the way things were shaping up due to Varro’s insistence on fighting on the flat ground, Paullus refused. The next morning, when Varro resumed command, he stacked his forces in three deep phalanxes with the hope of seizing upon the center of Hannibal’s line – the area which had collapsed at Trebia. Intent on pressing the numerical advantage, Varro believed he could back the opposition up against the Aufidus River and then slaughter them as they attempted to cross to safety. As if he sniffed Varro’s strategy out from the beginning, Hannibal decided to employ the weakest of his troops in the center, standing relatively inexperienced Gauls and Iberians in front. He then staggered the remaining soldiers – those from Carthage experienced in battle – at an angle to either side, spreading the inferior numbers out so as to be wider than the Romans and prevent any flanking maneuvers. Varro was unknowingly leading his men into one of the most impressive traps ever created on a battlefield. The Roman legions pushed forward into the center, executing Varro’s plans to perfection. Watching Hannibal retreat with the Gauls and Iberians behind him – a controlled movement decided to flatten and extend the Carthaginian line – gave the Roman soldiers hope their army would again be victorious, not least of which because the battle was on home soil and closer to the capital than any before it. Pushing further and further into the heart of the opposition, it seemed as though triumph was inevitable. Hannibal’s men, now spread out in a semicircle with the enemy pressing toward the middle, performed a double envelopment, closing the ends and pinning the Romans in the center as the Gallic, Iberian and Numidian cavalry attacked from the rear. Seizing on a lack of discipline in Rome’s lines (soldiers had begun shifting closer together as the “opening” created by Hannibal took shape), the armies of Carthage began cutting through the enemy without remorse. Only 14,000 Romans would survive out of more than 85,000 that had made the attack, eventually shamed for desertion and sent to Sicily for the remainder of the Second Punic War. As proof of his success, Hannibal sent more than 200 gold rings worn by the Roman aristocracy to the Carthaginian Senate, ordering the jewelry pulled from the fingers of the dead be poured on the floor. Over the course of hardly more than a year and a half, Hannibal’s victories had resulted in the deaths of one in five Roman men over the age of 17 – with close to half of the casualties happening at Cannae alone. Legend has it that every person in the capital knew at least one man killed. The historian Livy wrote, “Never before, while the City itself was still safe, had there been such excitement and panic within its walls.” Tired and battle-worn, Hannibal’s army returned to Carthage with a new spate of allies in southern Italy. Cannae would be the closest he ever came to Rome.

August 2, 216 BCE – Hannibal Causes Panic in Rome After Victory in the Battle of Cannae

Click to view full Infographic In the southeast of Italy, approximately 170 miles from Rome, the tiny town of Cannae would be the scene for the last major threat to…

408